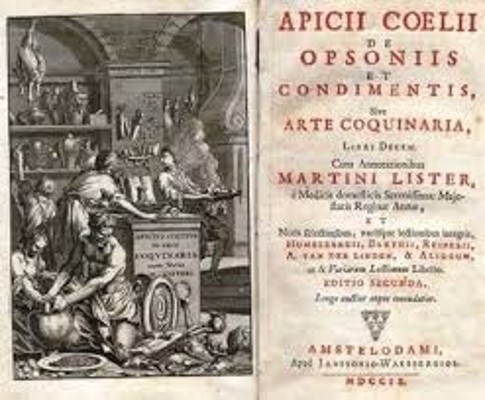

Pasta is the main food for most Italians, perhaps the one that best identifies Italianness in the world. Many believe that the origin is Chinese, but in reality the history of pasta begins in more remote times, dating back, as some say, to around 7000 years ago, or when man began to abandon the nomadic life and become a farmer. The history of pasta begins with the harvest of wheat, wheat which, from generation to generation, man has learned to work better and better, grinding it, kneading it with water and then flattening it and cooking it on hot stones (we saw in another article that this was also the origin of pizza). There is evidence that the ancient Greeks and Etruscans were already accustomed to the production and consumption of the first types of pasta, which certainly were not spaghetti (later we will see why). The Greek word leganon was used to indicate a large sheet of pasta then cut into strips. Even in the Roman Empire we find the leganum, sheets of pasta that conquered the taste of the people.

It seems then that it was the Arabs of the desert who first dried the pasta for better preservation, also because on their travels they did not have enough water to produce fresh pasta every day. They were the authors of the first “macaroni”, small cylinders of pasta with holes in the middle for rapid drying.

Palermo is historically the first true capital of pasta as the first historical evidence of dry pasta production at an artisanal-industrial level refers to the 11th century in Sicily, a region then deeply influenced by Arab culture, and in the first cookbook Arab, Ibran’al Mibrad already describes different shapes of pasta. Around 1154 AD, there are writings that report that in Trabia, a town near Palermo: “pasta in the form of threads, called triyan, is manufactured and exported to various parts of the Muslim empire and to the rest of Italy.

Another region that became famous a few centuries later (13th century) for the production and trade of dried pasta is Liguria, probably feeling the influence of Sicily following commercial contacts. However, the culture of dried pasta does not appear to be present in much of Central-Northern Italy, more linked to the domestic use of fresh pasta. The “pasta makers’ guild” was founded in Genoa in 1574, with its own statute. While in 1577, the establishment of the “Regulation of the Art of the Fidelari” was recorded in Savona (the term “fidei” indicates “pasta” in the local dialect. This was followed by that of the “Vermicellari” in Naples in 1579 and in Palermo in 1605).

In 1890 there were 222 pasta factories only in the province of Genoa and 148 between Savona and Imperia. But then the scepter passes to Naples. And twe have to think that in the 16th century Neapolitans were called “leaf eaters” for their diet based mainly on vegetables (primarily cabbage), bread and meat. It will only be in the 18th century that the epithet of “mangiamaccheroni” passed from the Sicilians to the Neapolitans, a popular diffusion of the food, therefore, which previously, in southern Italy, was reserved for the richest, considering pasta a whim, a luxury. And so the pasta-cheese combination takes the place of the traditional cabbage-meat combination. An ideal nutritional solution given that cheese provides proteins and fats that are missing from cereals which are instead rich in carbohydrates or sugar. This prevents the phenomenon of malnutrition, a scourge of the time in most part of Europe, also due to the ongoing demographic explosion, as happened in northern Italy, with the main diet based on corn (polenta) or in Ireland with potatoes.

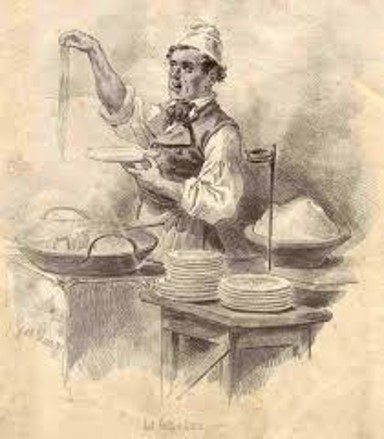

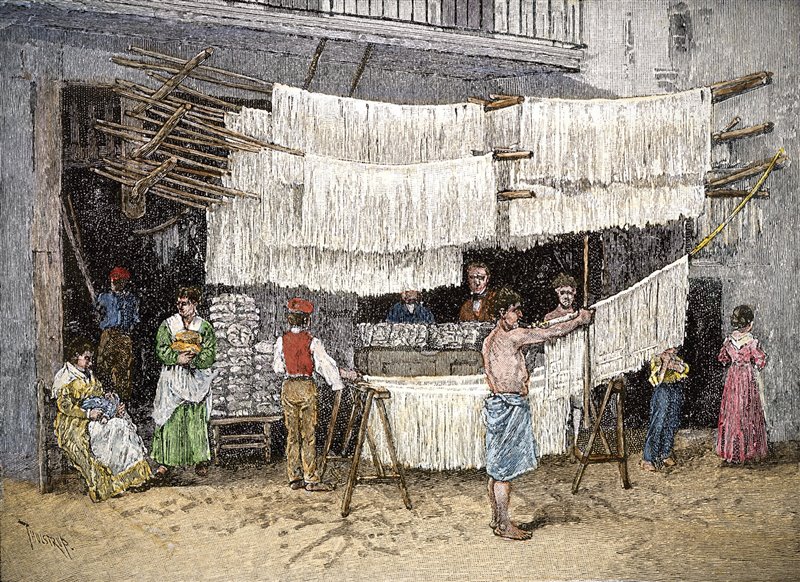

It is therefore precisely in Naples that the “second” introduction of pasta into Italian food culture and popular consumption begins. Pasta can be bought ready-made in the kiosks along the streets and eaten with your hands, without seasoning or with cheese (hence the expression “like cheese on macaroni”). Only in the 19th century the tomato was introduced (remember that, as already written in the article on the history of pizza, the tomato was introduced from the Americas only in the 1500s and was initially greeted with distrust because it was considered poisonous). And it will be in Naples that the production technique and perfect drying of the pasta is perfected in order to avoid the natural fermentation that would have made it rancid. And atmospheric conditions play a decisive role in this process: you need a ventilated, non-humid and sunny site, a place where changes from humid to dry weather are rapid and frequent. And the area between Gragnano and Torre Annunziata was the one that most reflected these peculiarities.

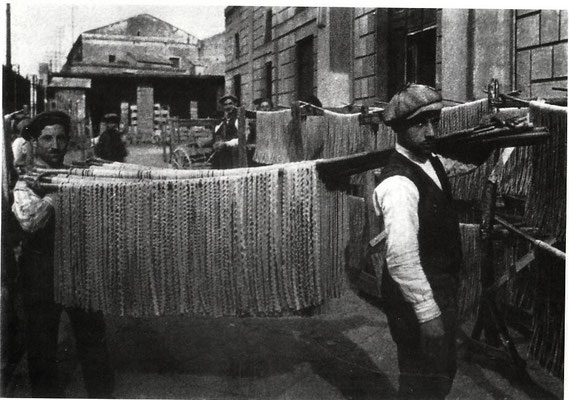

The industrialization of pasta along the Neapolitan coast has been impressive since the mid-19th century. Until then, mills and millstones were used and the semolina was separated from the bran by skillful manual sieve work. In 1878, a machine was introduced that improved and speeded up production: the purifier, known as the “Marseillaise” as it was invented in the French city. Since then there has been a continuous mechanization and modernization of production which inevitably, already from the early 1900s, made the meteorological characteristics of the place of production less and less binding and even less so after the development of a thermodynamic system for the artificial drying of pasta, a machine invented by a technician from northern Italy, a certain Garbuio. Then in 1933, with the introduction of the continuous mechanical press, there was an almost complete mechanization of production: semolina entered the machine and the pasta came out ready to be dried. The loading/unloading operation of the pasta on the drying frames is still manual, with still long times (over 24 hours) and with temperatures that should not exceed 40°C. It was after the Second World War (late 1950s) that the two processes were unified in an automated manner. As we said at the beginning, the first pasta was made by hand and for this reason the only possible shape was the tagliatella-fettuccine type, as the dough was flattened and reduced into thin sheets then cut into more or less wide strips. Spaghetto, like the other 300 shapes of pasta, is the product of the machine and for each shape there is an ideal seasoning. Today pasta is the most popular Italian food in the world and on 25 October World Pasta Day is celebrated all over the world! To date, Italy still maintains its role as absolute leader in the production sector (first in the ranking with 3.6 Mton in 2022), but we are also the country that consumes the most (estimated 23kg per capita/year). The event was born in 1988 with the 1st international congress held in Rome.

And the myth of China and Marco Polo? It was a stupid marketing activity in 1929 by the “Macaroni Journal”, the magazine of the American Association of Pasta Producers which attributed the invention of the long strings of pasta to the Chinese. It would then be a sailor from Marco Polo, with the unlikely surname of Spaghetti, who stole the recipe which the Venetian traveler would later spread to Italy. In the opera “Il Milione” the wonders of distant countries are described, but in all the manuscripts of this work there is no news about “spaghetti”, while it speaks of sago flour extracted from a particular species of palm that the inhabitants of Sumatra use to make lasagna and other types of pasta. The misunderstanding arose two centuries later, when the diplomat, geographer and humanist of the Republic of Venice Giovanni Battista Ramusio, publishing Marco Polo’s travel memoirs, misunderstood and manipulated the text and attributed the information on sago paste, which he had brought a sample in the Serenissima, to pasta in general, making people believe that the ambassador to the court of the Great Khan Kubilai had discovered the secret in the land of Confucius. However, in China there are testimonies dating back to the 2nd-3rd century AD of a sort of elongated pasta, spaghetti, made with soy or spelled instead of durum wheat, a creation and evolution different from the Mediterranean one.

NUTRITIONAL VALUES

On average, 100g of pasta provides approximately 370 calories. and of these 82.9% are provided by carbohydrates, 13.7% by proteins and 3.4% by fats. The main nutrients per 100 g of pasta are:

water: 9.9 gr

proteins: 13.04 gr

fat: 1.51 g

carbohydrates: 74.67 g

Leave a Reply